As part of our ongoing research to develop innovative later living schemes in our towns and cities, Urban Edge’s Sonia Parol has visited care homes and later living schemes in Europe that are taking a different approach to those found in the UK. In the first of three blogs, Sonia shares some of her observations from two urban care homes in Copenhagen that actively encourage social connection through the provision of shared and social spaces.

One of the key observations we made at the recent Housing LIN conference was that the later living sector in the UK is at a pivotal moment: it is a sector that recognises the changing needs and expectations of its core demographic and is interested in innovation and evolution. Yet to do this, it must seek to challenge the rules and change the concepts that we have been applying to later living schemes for years.

That the sector is poised to embrace innovation was good to hear as it backs up our long-held view that we need to find innovative new solutions for the people coming into retirement age now as they will have completely different lifestyle expectations to those that went before. For some time in the UK, the retirement or care sector has been focused at the high end of the market – luxurious care and retirement villages, often located in rural locations. These developments may suit the silent generation, who perhaps haven’t travelled far and have worked and saved to feel safe and secure; but the baby boomers who are now entering retirement, who were brought up in the revolutionary era of The Beatles and the Stones and have often travelled widely are increasingly demanding the opportunity to engage in the social and economic life of the wider community. They want to live in urban and suburban areas and continue to lead an independent lifestyle, maintain and build new friendships, participate in community activities.

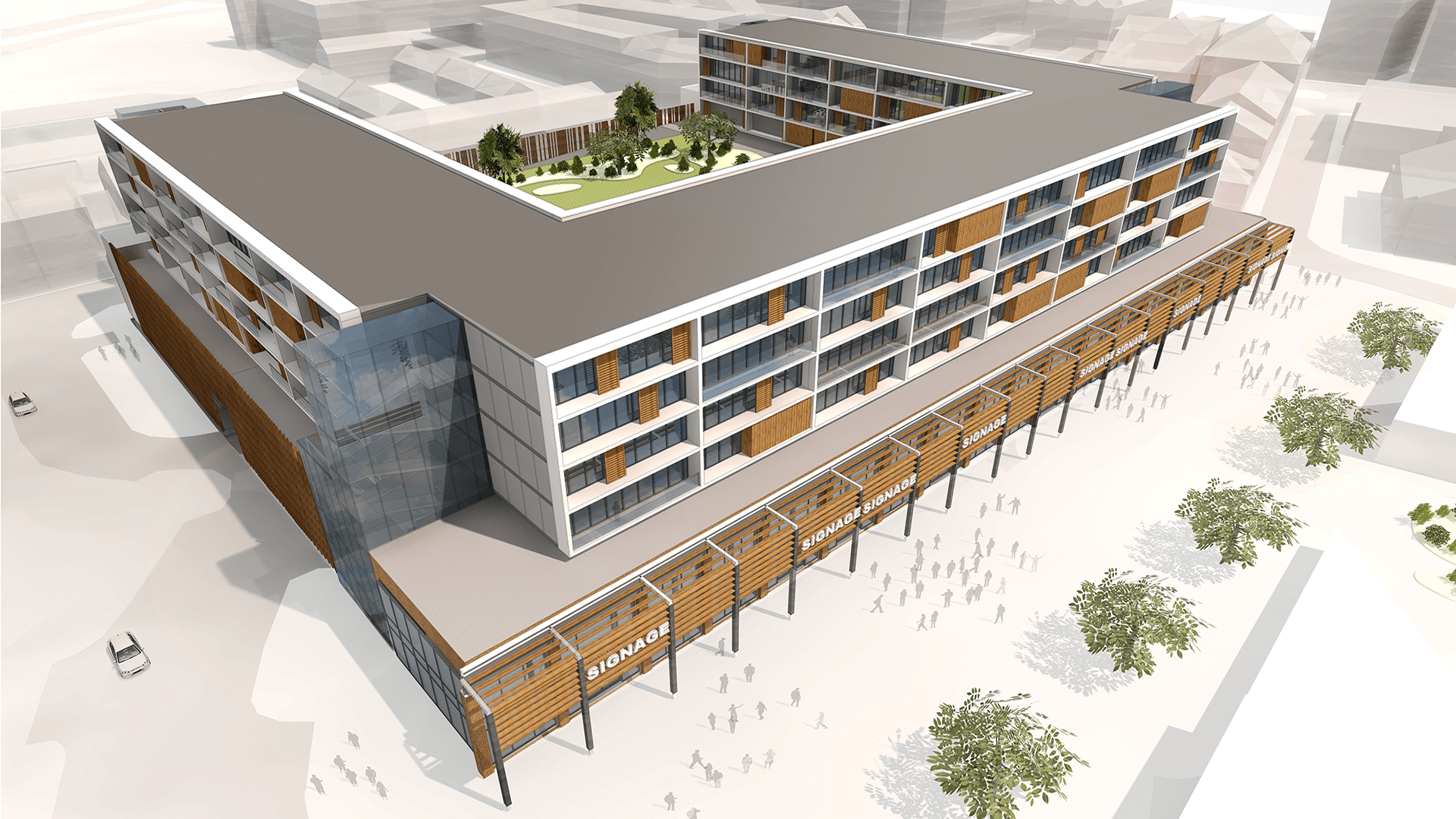

At Urban Edge Architecture we are interested in developing innovative later living schemes in our towns and cities that actively encourage social connection through the provision of shared and social spaces. We want to create communities where young and old can live side by side, both benefiting from the social, cultural and economic opportunities of a multigenerational community. We are therefore always keen to further our knowledge of these types of development and, over the last six months, we have travelled to other parts of Europe to visit care homes and later living schemes where there is a physical connection with the wider community. This ongoing research not only allows us a better understanding of the advantages of these schemes, but also to consider the challenges and how these could be overcome. After all, as physicist William Pollard once famously said: “Learning and innovation go hand in hand.”

In September last year we embarked on a study tour to Copenhagen where our first port of call was to OK Huset Lotte in the Frederiksberg district of the city. This state-funded, 60-resident dementia care home lies just 15 minutes’ car journey from the main city centre and, upon arrival, it is immediately striking how different a model it is to those that we see in the UK. Lotte is designed over six floors and is very contemporary in style – the furniture, for instance, is very modern and minimalistic in keeping with the Scandinavian vernacular. The reason for this is simple: the majority of the residents were from Copenhagen and would have lived in apartments in the city before moving to Lotte and therefore the surroundings and living accommodation would have been recognisable to them.

The ability for residents to remain in the area where they had lived also meant that their neighbours who were still living independently could easily come to visit, ensuring a continuous and seamless connection to their local community. Whilst much store is set, quite rightly, on maintaining connections with family, it has to be recognised that a connection with your neighbours and friends is also very important. If you remove a person from one place to live in a care home that is 100 or even 50 miles away from where they were living then you break their connections with the community. In Copenhagen, having care homes in rural locations as well as in city centres and other urban locations gives people a choice to remain in the community in which they lived. This couldn’t be in starker contrast to many of the later living and care home facilities we see in the UK, which often isolate older people from their local communities.

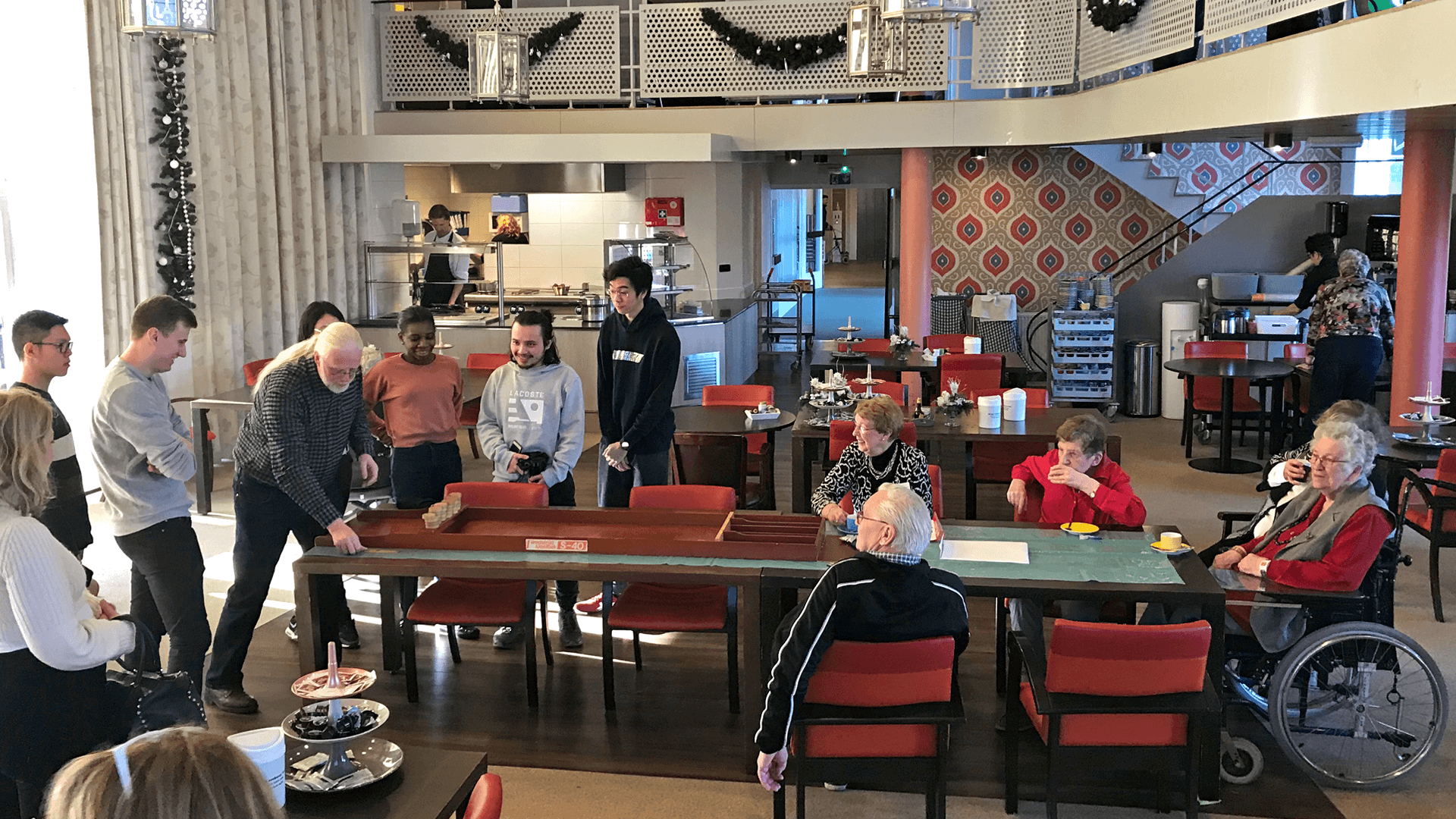

Physical connection to the local community couldn’t be better exemplified than at the Bomi-Parken care home we visited next on our tour. Part of the Gyldenrisparken residential complex in Copenhagen, at Bomi-Parken there are no fences or gates and the care home is physically linked with the housing and schools that surround it, as well as being near to a local neighbourhood shopping centre. The elderly can interact with families and children going about their daily activities and greatly helps to combat loneliness and keep minds active.

Lars Bo Sørensen, the Manager of Bomi-Parken, told us that visual and physical connection with the local community was the key design element when they considered the scheme. He said that the people who live around the care home use the facilities – they come in to use the gym and the café; they come in to use the food therapy room and the diabetes clinic. This is in marked contrast to care homes in the UK, where shops, hairdressers, cafés and therapy centres may well be included, but are often enclosed within the development – not facing a public square and local shops to be used by the local community.

Visual and physical connections are maintained in other ways, too. Residents of the care home could see and hear children at play in the adjoining school playground. A zipwire, running just 10m away from the windows of the care home, had children zooming along it; rather than it being annoying, the sound was happy and people from the care home were sitting on balconies watching, smiling and laughing. In many ways, it was really overwhelming to see the joy this brought to residents.

Observing the residents of Bomi-Parken choosing to sit on their balconies, go down to the garden, or visit the local shops, it struck me that in a lot of care and nursing homes in the UK, people don’t have a need to leave their bedrooms as there isn’t much activity – and the activities that are provided sometimes feel institutional and involve little personal choice. Yet even facilitating a visual connection to the activities taking place in the local community can create tangible benefits, giving residents a choice to observe the world around them and feel like they are part of it as well.

One of the other key aspects noted during our Housing LIN conference workshop on the future of later living, was that we need to spend less time focusing on age and more time on individual needs and lifestyle. From a design point of view, therefore, it was interesting to note the differences between Bomi-Parken and OK Huset Lotte and how they have been planned to reflect the lifestyle of the residents.

Bomi-Parken care home is a two-storey building because the surrounding residential area is much lower rise and the interior is much softer than the contemporary designs found at Lotte. Bomi-Parken also has a much larger garden area because residents, having lived in the surrounding suburbs, were used to having gardens and seeing green open space. Lotte, on the other hand, was located in a town centre and only had a roof terrace and balconies. Also interesting to note was that, at Lotte, there were two key areas with large windows – one to watch a railway track and the other overlooking a very busy road where people would choose to sit and watch the city life because that’s what they were used to doing; whereas in Bomi-Parken it was completely different, with views from windows looking out over the school playground, the zipwire and the square as one might expect in suburbia. When you analyse the social context you are able to design a building fit for purpose, creating a recognisable environment and a normal life for the residents.

Whilst we are starting to see more interest in locating care and later living accommodation in urban areas in the UK, the focus tends to be on extra care or at the luxurious end of the scale, particularly in the South East. Care homes are still generally located in more rural and quiet locations. There is clearly a need for these rural developments, but people are increasingly demanding choice. Somebody who has lived all their lives in a rural area wouldn’t want to move to the city centre, whereas people who have spent all their lives surrounded by cafés and shops and the buzz of the city wouldn’t want to move away to the quiet country life.

Likewise, ageing impacts every social strata and it is our view that we should be looking into more mid-market models and maybe look for inspiration in some of the Scandinavian and Dutch approaches? These two developments in Copenhagen demonstrate what can be achieved – whilst our follow-up study trip to the Netherlands afforded us even further opportunity to observe approaches that allow for multigenerational integration and connections with the wider community through communal services. You can read all about that trip in Part II of this blog, coming soon…

We would like to express many thanks to Anna Wilroth from Aeldre Sagen (Dane Age) who helped us organise our trip to Copenhagen.

Sonia Parol | Senior Associate Director