Plans submitted for visitor destination and education centre at Harlaxton Manor

September 8th, 2022 Posted by Urban Edge All, Landscape, NewsWe have submitted a planning application to South Kesteven District Council on behalf of Harlaxton College for the restoration of the disused Walled Garden at the historic Harlaxton Manor, near Grantham, to create a stunning and sustainable visitor attraction and educational experience.

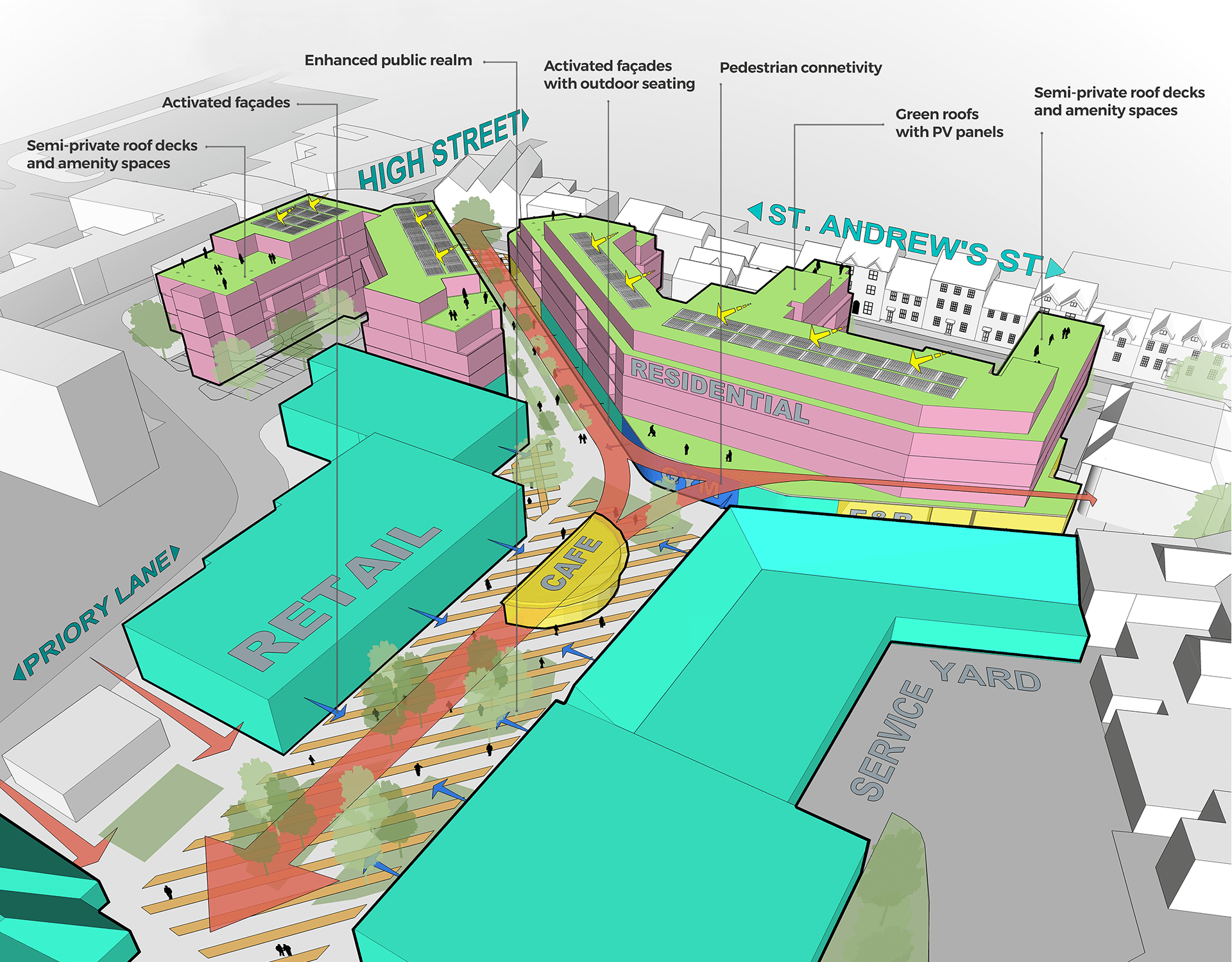

As Landscape Architect and Project Lead, we worked in close collaboration with Harlaxton College to create a masterplan for the 56.65ha site and a detailed landscape design focused around the historic Grade II* Listed Walled Garden, which will not only restore the historic fabric, but recreate the original productive function of the garden and introduce opportunities for education and participation. The proposals have been submitted following extensive engagement with stakeholders and with representatives of the community and officers of South Kesteven District Council, Historic England and Lincolnshire County Council.

Andrew Cottage, Head of Landscape Design said: “This is an exceptional project in which we have applied our landscape design skills and understanding of the historic environment to deliver a practical and beautiful scheme that will meet the needs of the College and satisfy the requirements of Historic England and the planning authority. On completion the public will have access to assets of heritage significance which have previously been inaccessible to visitors helping them to understand, appreciate and interpret the past.”

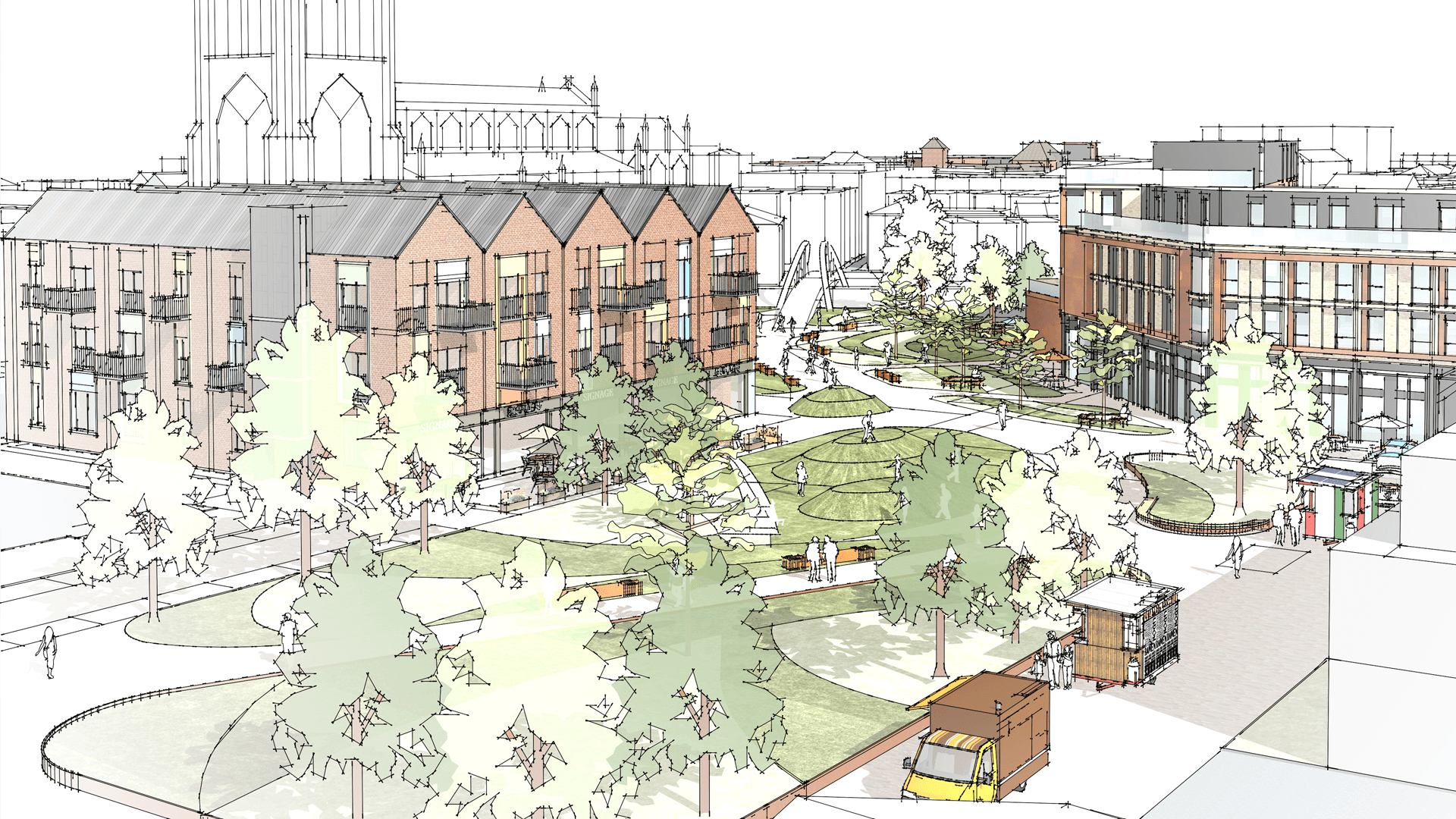

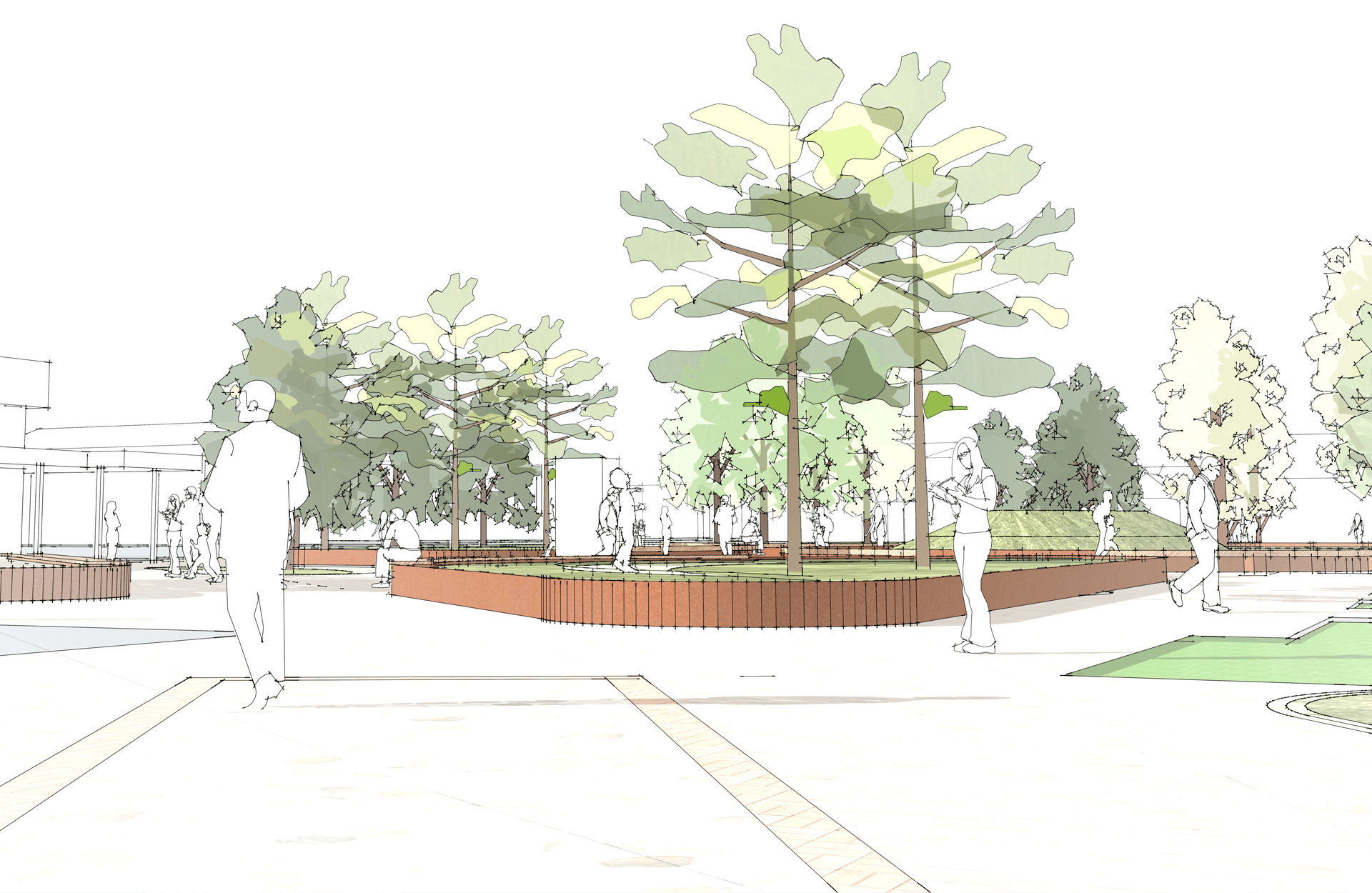

The Walled Garden will be made fully accessible and will be arranged around a series of axial vistas dividing the area into a series of garden rooms, each with a different character. Some areas will focus on the historic roots of the garden, emphasising the production of fruit, vegetables, herbs and cut flowers, with others being themed with specialist planting, such as four seasons, medicinal and sensory gardens. Tall hedges aligned with the axial paths will introduce a sense of intrigue and drama by not allowing the whole garden rooms to be seen at once and will create a sense of arrival in to the next character area.

The scheme includes associated visitor infrastructure such as a new car park; footpath network and play area, whilst a large lawn will create a flexible space for informal gatherings and more formal events such as performances and parties. The listed Gardener’s House is being restored and converted by HP Architects into a new café, visitor facilities and education centre. The two historic vineries will be sensitively replaced and will serve as a café seating area with splendid views across the gardens and an education centre.

Despite the challenges of working with heritage assets, sustainability was a key focus of the design, which included elements such as green roofs, ground source heat pumps and solar panels on the roof of the new energy centre. EV charging points will be included in the car park and the whole project is targeting BREEAM Very Good.

Concludes Andrew: “This is a remarkable opportunity for us to be involved in a very exciting project to restore an historic walled garden and make it relevant in the 21st century, creating opportunities for education, participation and horticultural innovation. It was immensely rewarding to lead and coordinate such a talented multidisciplinary design team to achieve such an impressive outcome.”

Our design is part of an on-going process by Harlaxton College, the overseas study centre of the University of Evansville, in close liaison with Historic England, to restore and preserve the historic features within the estate and remove the Grade II* listed grounds and gardens from Historic England’s Heritage at Risk Register.